About

Overview

This Online Archive of the Centre for Contemporary Art and the Natural World has taken longer than I anticipated. After CCANW was dissolved at the end of March 2020, I secured funding from Bath Spa University in the following year to begin the process of bringing together copy and photographs from former staff, notably Chris Lewis, Johanna Korndorfer and Martyn Windsor, and artwork from our designer Robert Shaw. My sincere thanks go to them all, and to the many other Trustees and colleagues who have contributed to the writing of chapters.

Because of the period of 25 years that this Archive covers, and my own poor memory, I have had to rely to a large extent on CCANW publicity, minutes of meetings and financial accounts. From these, I have prepared the greater part of the copy. From photographs, some with embedded dates, I have been able to match to activities with the help of Conrad Bohl. Only now, in April 2023, am I beginning to work with our son Tom Adams on assembling the different parts of the Archive.

This summary follows the chronology of the chapters and the programmes we have put together over the years. I would like to thank all the artists and curators with whom we have worked, and the many thousands of visitors and participants who have engaged with our work. All this has largely only been possible because of funding from Arts Council England (ACE), trusts and foundations, and (in the early period) European Union and District and County Council sources.

It is impossible not to recognise that CCANW has gone through difficult and challenging times but this is not uncommon and will be articulated in the following conclusions, from which lessons will hopefully be learnt!

Arnolfini and CCANW

Although I have acknowledged the influence of Jeremy Rees, co-founder of Arnolfini who continued as its Director until 1986, there were several basic issues that Jeremy got right and I got wrong.

Firstly, Jeremy developed Arnolfini in stages from the start, whilst it was not until withdrawing from Poltimore and becoming established at Haldon from 2004 that CCANW adopted this strategy.

Jeremy limited himself to Bristol, a City he knew well and which knew him. I, on the other hand, looked across the whole of Devon for potential sites and partners, having only moved there in 1997.

Jeremy had the support of benefactors, and generated a good proportion of Arnolfini’s income from the sale of prints and other artworks to collectors in the early years. It was not until our Poltimore era that the prospect of serious patronage was offered (but not followed up), and the nature of the work CCANW exhibited was generally less commercial.

Once established, Arnolfini became funded on a regular basis by ACE which was an advantage in attracting grants from other sources, whilst CCANW was only funded project by project, mainly on an annual basis.

1996-97

The Dunsland Project

As its first choice of location, Dunsland had many advantages. In the National Trust it had a powerful owner who shared many of our environmental objectives. Establishing ourselves in an under-provided area of Devon made it attractive to many stake-holders, including ACE, the district and county authorities, as well as business and tourism interests.

The overwhelming problem was the response from the local community who only became aware of the project when funding for a Feasibility Study had been secured from Torridge District Council (TDC) and ACE. Because the initiative had come from an individual who was not from the area (at the time living in Hertfordshire), it was easy for opponents to circulate misinformation. There was also misunderstanding as to what a Feasibility Study entailed; those who wished the Study to go ahead felt aggrieved that the most vociferous group blocked the beginning of a fully-funded objective and democratic process.

Had TDC been allowed to conduct its Feasibility Study, it could well have found the project eligible for funding from the European Union and there would have been a number of options for the design of a new building.

Having said that, with the benefit of hindsight, CCANW would probably have struggled, without a generous benefactor, to attract sufficient paying visitors to make the location viable.

1998-2003

Poltimore House

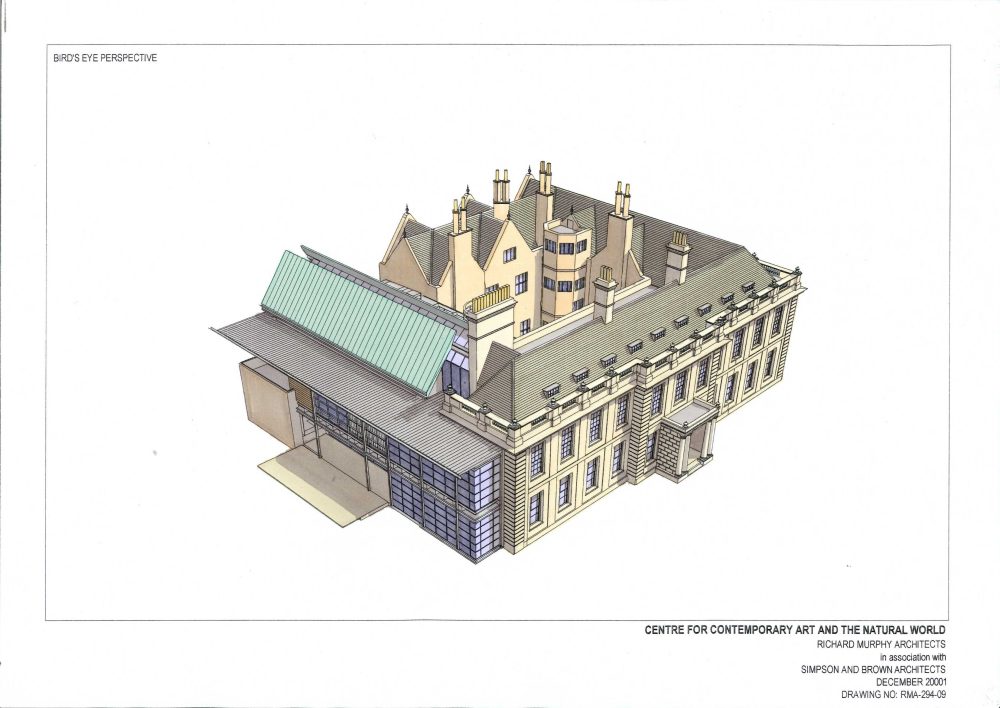

Whereas Dunsland offered the opportunity to create an entirely new building, Poltimore was a large historic building in very poor condition for which a new use had eluded the local authority and heritage bodies for many years. Although the architectural team we had brought together came up with a brilliant scheme, there was no disguising the fact that this was a considerable challenge and one that could not be undertaken in phases.

Although East Devon District Council put up funding to support our arts and heritage applications to the National Lottery, no major patron emerged and the building and land were never adeqate to generate capital or revenue from a developer or through tenancies.

Our original understanding from ACE was that in order to apply for funding for any ambitious capital scheme one should have undertaken detailed Feasibility and Development Studies. This was what we completed, only to be told by ACE that the process had changed and nothing was required beyond the completion of a simple form. If a project was accepted, ACE would work with the applicant to find a building and devise a business plan, and then move on to the next stage. Quite clearly, CCANW stood no chance of success with a very expensive capital scheme and an unproven business plan.

Despite that, had we first secured the majority of funding to conserve the historic house from the Heritage Lottery Fund and English Heritage, ACE might well have been more sympathic to our application.

In recent years, Poltimore House Trust, which had been established in 2000 to own the freehold, has succeeded in attracting funding of over £300,000 (mainly from English Heritage) in order to protect the building with scaffolding and corrugated metal panels. The conservation architects are still involved, and there is a thriving Friends group of volunteers drawn from the local communitity.

2004-13

Haldon Forest Park

Our establishment at Haldon Forest Park fulfilled two requirements that were important to CCANW. The Forestry Commission had already secured funding from Sport England to deliver visitor infrastructure, and were agreeable for us to be developed in phases.

In a first phase, a redundant timber building was converted with the aid of a range of grants. The location for a second phase building was identified, but FC funding from the Government declined, the key Regional Director took early retirement, and this was never achieved.

The so-called ‘black shed’ opened in 2006 and its small but dedicated staff organised a number of successful exhibitions and activities that were popular with visitors and participants. These ranged from artist residencies, commissions, long-term projects and exhibitions (some of which toured), often grouped together in thematic programmes involving guest curators, and supported by learning opportunities, talks, live music and films.

The main programme themes can be summarised as University of the Trees (2006-11), Forest Dreaming (eight parts 2006-7), Wood Culture (five parts 2007-8), Greenhouse Britain (2007), Haldon’s Hidden Heritage (2008-9), The Animal Gaze (six partners 2009), Local and International Artists (five parts 2009-11), Fashion, Textiles and the Environment (four parts 2010-11), Tree Culture (three parts 2011-12) and Games People Play (two parts 2012-13).

Unlike Poltimore, the challenge at Haldon was not a matter of capital costs, rather one of revenue. The building at Haldon was not large enough to generate income from admission charges, so was largely reliant on grant aid. In our case, we were advised by ACE to initially apply on an annual basis through Grants for the Arts (GfA). In due course, if we became successful, we could apply to become a National Portfolio Organisation (NPO) like Arnolfini.

Our intention was to secure sufficient match funding and the value of support-in-kind to apply to GfA for around half of our income. The GfA scheme was ‘project based’, so our programme was deliberately different from one application to the next. It was not designed for an organisation that had ongoing staff and building overheads, as we did. If an application failed because of low match funding, as it did in 2010, it created a crisis.

GfA was clearly not an appropriate scheme to fund CCANW indefinately and in 2011 we made an application to be part of ACE’s National Portfolio of regularly funded organisations for the three years 2012-15. ACE’s stage one assessment recommended support at the full amount requested, but at stage two the ‘panel preferred other organisations on geographical spread and artform’.

Of course, issues around lack of funding from ACE and trusts were not the only major external financial problems that led to us having to leave Haldon. In 2002 and 2007, the South West Regional Development Agency (SWRDA) had supported our establishment and programme with two grants totalling £109,144. Between 2004 and 2012, we benefitted from 12 other rural regeneration, development and enterprise grants from the European Union (EU) and SWRDA totalling £175,775. With the abolition of Regional Development Agencies by the UK Government in 2012, these dried up completely.

Grants from local authorities also declined after 2008/10 due to Government cuts. Up to 2010 CCANW had benefitted from five grants from Devon County Council totalling £28,250. After 2008, grants for the arts from Teignbridge District Council dried up completely.

In 2013, the failure of our GfA application for the Soil Culture programme led to CCANW having to abandon our building, make staff redundant and leave Haldon.

The news in April 2023 from the Forestry Commission is that a new visitor centre is to be built at Haldon and they are erecting signs along one trail based on the exhibition panels CCANW made for Haldon’s Hidden Heritage.

2013-15

Innovation Centre

The ground had already been prepared for a move from Haldon to offices at the Innovation Centre at the University of Exeter. This involved curating a series of 15 exhibitions in the foyer/café, and the delivery of the different phases of Soil Culture. Unfortunately, despite our best endeavours, the departure of our key contact Dom Jinks in 2014 inhibited any other deeper engagement with the University.

Soil Culture (2013-16) marked a major change in CCANW’s partnership working which involved the different parts of the programme being delivered in different places and funded in different ways.

The first phase was a Forum at Falmouth University largely funded from a grant from the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC). The second, Young Shoots, a phase of international artist residencies and a resulting touring exhibition, part funded by ACE with match funding coming from all the hosts and venues. The final phase Deep Roots, because of the failure of our grant application to ACE, was only achieved through direct funding from the two gallery venues in Falmouth and Plymouth, and with CCANW staff working with little or no pay.

Fees from many different partners in the Young Shoots phase meant that the challenge of raising match funding to support the application to ACE was solved. However, when exactly the same strategy was followed for the next Deep Roots phase, the application failed and CCANW was forced to leave the Innovation Centre.

Despite the United Nations having designated 2015 as the International Year of Soils, we were truly shocked at the lack of other initiatives and of any financial support from the UN, DEFRA or any other agency or trust engaged in environmental issues in the UK. The exceptions to this were the British Society of Soil Science and the Heritage Lottery Fund, with whom we went on to work on the Our Living Soil programme.

The Young Shoots exhibition was launched in Bristol at the Create centre in 2015 but, despite being designated European Green Capital, we received no financial support from the City and it was only due to the lively programme of Soil Saturdays led by Touchstones collaborations that it engaged so well with the community.

2015-20

Dartington

The invitation from art.earth to move our base to Dartington to become part of a ‘family’ of like-minded organisations held significant appeal and a Memorandum of Understanding was agreed with Schumacher College in 2015, but lapsed after the departure of its Head in 2018.

This was a phase during which CCANW attempted to increase its international and transdisciplinary working. I already had excellent contacts in South Korea and the Science Walden project agreed with Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology brought substantial new income. The project required the Lead Researcher to hold a Doctorate, so Dr Richard Povall took the lead whilst I tried to develop projects with new partners, notably the Global Network of Water Museums in Italy. Part of the fee from UNIST was used as match funding for the unsuccessful application Across Borders to ACE which could have supported collaborative projects between the UK, Korea and Italy.

During this phase, plans for Schumacher College to deliver a new MA/MFA Arts and Ecology course were abandoned. The gallery previously used for exhibitions by art.earth became a café. Our proposal to establish High Cross House as an International Centre for Ecological Arts and Radical Thought was not accepted by the Dartington Trustees and, at the end of the MOU, CCANW was asked to remove its books from the Elmhirst Library and its files and equipment from storage on the Estate.

Sadly, at the end of 2022, faced with their own financial challenges, the Directors of art.earth decided to dissolve the Company in the following year.

2004-22

CCANW and other Associations

Spanning the period from Haldon to Dartington and its dissolution in 2020, CCANW had associations over a number of initiatives, some of which were developed into funded projects.

Research in Art, Nature and the Environment (2004-15) was a research group led by Daro Montag (a CCANW Trustee 2013-20) at Falmouth University which was instrumental in organising a number of important symposia and the setting up of the MA Art and Environment. Sadly, the University closed both it and the course in 2015. RANE’s last act was to secure the substantial AHRC funding of Soil Culture.

The Arts and Environment Network (2007-on going) was a UK network set up under the auspices of the Chartered Institution of Water and Environmental Management (CIWEM) which initially met regularly at their headquarters in London. From 2008, Dave Pritchard (a CCANW Trustee 2009-13) was the Network’s Chairman. It began making an annual award in association with CCANW in 2010 and produced its Manifesto in 2012. It never secured funding for its activities and, since CCANW’s dissolution and the start of Covid in 2020, it has not met or made an award.

The Global Network of Water Museums (2016-on going), based in Venice, was introduced to CCANW through my attending the Festival of the Earth in 2016. Initially, a proposal was made for a major exhibition at the time of the Venice Biennale but the level of sponsorship was unachievable. Through meetings held in Venice, the Netherlands and Spain, I and other guest artists and curators made presentations to representatives from water museums, for which their expenses were paid. Since the dissolution of CCANW, I have continued to advise in a voluntary capacity and in 2022 was one of the curators of the online exhibition I Remember Water.

I also visited the Botanical Gardens in Padua in 2016 and was impressed by the potential of their new gallery. I wrote a paper describing how CCANW might help over the curation of exhibitions but no progress was made, most likely because of costs. However, encouraged by the model of the Art and Environment Network and Global Network of Water Museums, I suggested forming a Network of Botanical Gardens (2016-20) that might share the cost of touring exhibitions. I began by taking the Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens in Edinburgh to Padua in 2019 but since CCANW’s dissolution and the Covid pandemic no further progress has been made.

Jill and I had moved to Stroud in the spring of 2014 and I occasionally gave or organised talks at Stroud Valleys Artspace (SVA). These included Marlene Creates from Canada, members of Yatoo from Korea (both 2016), and Betsy Damon from the US (2019).

As an alumni of Bath Spa University, I took interest in the work of their Centre for Environmental Humanities and, along with Richard Povall, approached them in 2017 over the launching of a new MA Art and Ecology. Although this was not taken up, the University accepted the gift from Clive of CCANW’s former art and ecology library which is now housed at Corsham Court. A good relationship also developed with Ben Parry, leader of the MA Curatorial Studies, and BSU helped fund this Online Archive.

Our Living Soil (2019-22) was the arts programme initially devised by CCANW for the British Society of Soil Science (BSSS) to link COP26 in 2021 and the World Congress of Soil Science in 2022. Because both events were taking place in Glasgow, we proposed a focus on the City, Scotland and with organisations in Europe and abroad with an interest in soils.

CCANW applied to Creative Scotland (the Scottish equivalent of Arts Council England) for the funding of a research phase Sowing the Seeds and, since CCANW was dissolved in 2020, the application came for the second phase Reaping the Harvest from Our Living Soil, an Unincorporated Association. During the time of Covid, there was huge competition for funding from Creative Scotland and both applications failed.

Thankfully, the Centre for Contemporary Arts in Glasgow agreed to host and fund an exhibition co-curated by Alexandra Toland, and Propagate secured funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund for community activities.

Concluding thoughts

Waste takes many forms and Arts Council England/Creative Scotland grants, by their very nature, encourage competition over collaboration. Within their limited budgets from Government and the National Lottery, where many funding applications initially fail and require several re-applications before success is achieved (or never), ACE/CS could save itself and applicants huge amounts of time and effort by actively encouraging artists and organisations to collaborate. This might involve corporate amalgamations, the sharing of resources and the touring of exhibitions.

With a strengthening of its boards and staff to include people with a particular interest in the environment, the strategy of ACE, CS and its regional offices could also give some priority to the still relatively small number of arts organisations involved with artists over ecological issues.

Despite the escalating climate crisis and loss of biodiversity, the arts in the UK have been far too slow to respond to these environmental challenges in any significant way. Too many ‘art and ecology’ organisations (notably the Royal Society of Arts’ Arts and Ecology Centre 2005-10 developed in partnership with ACE) and courses have come and gone, or not been created in the first place. It is hoped that a survey of UK art and ecology organisations and courses will take place after this Archive has gone online.

As our final programme at Haldon Games People Play (2012-13) demonstrated, at the heart of today’s ecological crisis is our inability to be conscious of the forces that drive human nature and which determine the choices we make. A deeper understanding of the advantages of cooperation over competition, for instance, can help us address our needs and those of the planet at this time. Thankfully, there are now signs of adaptation and diversification with artists working collaboratively, across disciplines and with local communities. But it is still too little and, at present, one fears it may be too late to avert the worst consequences of environmental abuse.

From the start, the success of CCANW depended on a recognition that urgent environmental issues, particularly climate change and loss of biodiversity, were critical to the future of life on earth and that the visual arts were a powerful means to engage the public with these issues. CCANW has made some progress but that ambition and potential has sadly not been realised on the scale we first imagined.

Even in 2023, one learns of respected colleagues at art.earth having to close their company, and organisations addressing social and environmental justice such as ONCA in Brighton facing financial challenges.

With the benefit of hindsight, there are two final thoughts that could show a way forward:

The first is to propose the formation of an international network or agency of independent greencurators that are paid to curate exhibitions for public museums and galleries on ecological issues. The idea of an International Arts and Ecology Alliance was first discussed in 2010 by the Arts and Environment Network and the online greenmuseum.org. A CCANW Associate Artists and Curators group first met at Dartington in 2017.

The second is to propose the establishment of a high profile biannual International ECOART Prize open to artists or group of artists to work directly on new projects with communities and scientists around the work in addressing the climate crisis and biodiversity loss. CIWEM’s Arts and Environment Network has already made annual awards in association with CCANW between 2010-19, but the award was for past work and not financial.

Clive Adams 2024

Next Page

Team